The difference between rice for dinner and sakamai (sake brew rice).

Koshihikari is a famous rice to eat Shokuyōmai (食用米) and therefore known to many sushi lovers outside Japan.

For the production of sake, however, so-called "Sakamai" (酒米) are preferably used. Sakamai is thus an umbrella term for the genus of rice varieties that are particularly suitable for sake production.

There are two groups of Sakamai.

The most important group of sakamai is technically called "Shuzō-Kōtekimai" (酒造好適米) and includes rice varieties grown exclusively for sake brewing. According to the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, there were 223 rice varieties registered as Shuzō-Kōtekimai for 2019. Of these, about 100 varieties are currently in actual use & production. Yamada-Nishiki is by far the most common grade and the most widely used,

The second group of sakamai is actually grown for food, but can also be used for sake brewing. This group includes about a dozen varieties, interesting representatives of this group are for example Ōseto and Kame no o.

Even though both groups are suitable for sake brewing as sakamai, there is one major difference between the two:

Shuzō-Kōtekimai is much more difficult to grow and costs almost twice as much as edible rice (Shokuyomai 食用米).

The characteristics of suitable sake brewing rice

Steamed rice for dinner is often sticky, delicious, and high in protein and minerals.

However, sticky rice is not suitable for making sake because it does not produce Kōji easily. In addition, its high content of protein, fat and minerals makes it unsuitable for sake production. For these reasons, people take other types of rice for sake production.

Sake rice is typically 30% larger than regular rice, has a larger starchy core, and about 25% taller stems.

Shuzō-Kōtekimai rice varieties are characterized by their large grain, low protein content, and large "shinpaku" (opaque white rice center).

Cultivation of Shuzō-Kōtekimai costly and challenging in many cases.

The cultivation of Shuzō-Kōtekimai is considered particularly challenging: the rice ears of these varieties are much larger than those of eating rice varieties. For example, a common edible rice variety such as Koshihikari is about 90-100cm tall - but the rice varieties particularly suitable for sake are often 100cm - 150cm tall.

This is compounded by the greater dead weight of Shuzō-Kōtekimai rice grains, which overall encourages ear bending, especially during the typhoon season in Japan.

If rice ears bend or rice grains fall to the ground, this in turn attracts pests.

For the sake rice to be particularly good, it is still recommended to have a location that has a significant temperature difference between morning and evening.

Overall, then, there are numerous site factors and also considerable skill and experience required on the part of the farmer, which is what makes sake rice so costly in the face of low yield rates.

Typical Shuzō-Kōtekimai rice varieties that are especially suitable for sake

The rice used, of course, has a significant impact on the taste of the sake in question - but unlike wine, the other factors of water, yeast & koji, as well as the craft of the brewmaster, have a significant impact on the taste result.

Here we present some typical Shuzō-Kōtekimai as examples.

Yamada Nishiki rice - the "king" of all sake rice types.

Although common throughout Japan (especially in Hyōgo, Okayama, and Fukuoka), locally grown Yamada Nishiki (山田錦) produced in Hyōgo Prefecture is considered the best.

The climate and soil quality of Hyōgo Prefecture are perfect for growing Yamada Nishiki. Hyōgo Prefecture is the largest producer of this variety.

About 80 percent of Japan's total production is grown here. Yamada Nishiki was specifically developed in the early 1900s and contains a starchy core and only a small amount of protein and fat. This makes it perfect for effective fermentation.

The result is a pure, natural sake - fruity, fragrant, harmonious and smooth taste.

A worldwide already very well known representative of Yamada Nishiki sake is the Dassai sake from Yamaguchi Prefecture, for example Dassai 45 and Dassai 23.

Gohyakumangoku rice

Gohyakumangoku (五百万石) is a popular rice variety grown primarily in Niigata as well as in Fukushima and Ishikawa. It was registered in 1957 under its current name, which translates to "five million koku" or about nine million liters - commemorating Niigata's rice yield, which exceeded the five million koku mark that year.

Gohyakumangoku provides large grains weighing 26 grams per thousand unground rice grains (TKM 26g). In addition, it contains a large shinpaku, the starchy heart of the rice. This makes this particular rice variety ideal for sake brewing. The starch clustered in the center allows for effective removal of the outer layers of the grain (polishing), where proteins and lipids are found, which can lead to undesirable flavors. A high starch content also ensures a vigorous and stable fermentation, as starch is an essential source of nutrients for Kōji.

It took about 20 years for Gohyakumangoku to become mainstream. Its stable characteristics and high adaptability to mechanized brewing led it to have the largest acreage among sake rice varieties. In 2001, however, it was surpassed by the famous Yamada Nishiki.

Today, Gohyakumangoku is grown throughout Japan, but especially the regions in the northwestern prefectures of Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, Toyama and Fukui.

Gohyakumangoku is the basis for dry, light, refined and clean sake, symbolic of the Niigata style. Its refreshing flavor profile contrasts well with the rich and often full-bodied sake made from Yamada Nishiki rice.

Miyama Nishiki rice

Miyama Nishiki (美山錦) is the third most cultivated brewing rice after Yamada Nishiki & Gohyakumangoku.

When it was discovered in 1978 through a sudden mutation that exposed another rice variety, Takane Nishiki, to gamma radiation, the Shinpaku stood out: a "whiter than white heart" that can "rival the snow-capped peaks of the most beautiful mountain ranges." And so it was named: Miyama literally means "the beautiful peaks".

Although the main growing area is Nagano, it is grown in up to seven prefectures in northeastern Japan, including Iwate, Akita, Yamagata, Miyagi and Fukushima. Normally, the rice variety thrives best at higher altitudes, as it is resistant to cold.

What distinguishes Miyama Nishiki is its clean taste. It is an early maturing rice and is one of the first rice varieties harvested in the year. For this reason, it is a very hard rice. This means that it breaks down less easily in the fermentation mash and releases its flavor less dominantly in the final product. As a result, the sake this rice produces is more balanced, cleaner, leaner and smoother, with more mouthfeel but not as light in body as Gohyakumangoku - and still manages to impart enough inherent rice notes (grain-like notes) and quiet nose.

Omachi rice - diva of sake rice cultivation from Okayama

Omachi (雄町) from Okayama is the oldest known sake rice variety.

With no crossbreeding or genetic modification, this makes it the only "pure" rice variety in Japan. Omachi delights sake lovers and makers with its complexity and the fact that it is a variety that has been around for generations.

Omachi is quite "diva-like" both during cultivation and at several key stages of the brewing process.

It is a large-grained rice that produces excellent shinpaku. The presence of this translucent kernel is extremely beneficial at the important stage of Kōji production, as it helps the spores to grow. However, the disadvantage of this is that it grows on a very tall stalk, which causes various difficulties for rice farmers. Typical table rice comes from a stalk that grows about 70 to 90 centimeters tall. In comparison, Yamada-Nishiki, which itself is considered a very tall variety, can grow over 100 centimeters tall.

Rice with tall stems is usually late to harvest and is very difficult to harvest by machine. It can break frequently during the typhoon season in Japan. Considering that omachi can grow up to 150 centimeters tall, one gets an idea of the problems farmers face during cultivation. Because of these difficulties, omachi has now become so rare that it has been nicknamed "maboroshi," which roughly translates as "phantom rice."

Omachi is used for a whole range of sake types, including those that can be drunk warm. It is generally less fruity and floral, and more full-bodied, almost tart with a bit more earthiness. The flavors are generally less pronounced than sake made with Yamada Nishiki, for example.

Omachi fermentation in special bizen yaki vessels

Some of the sake made with Omachi are fermented in Bizen-Yaki vessels. Bizen-yaki is a type of Japanese pottery dating back to the 14th century originally from the province of Bizen (present-day Okayama).

The pottery is often characterized by an earthy, reddish-brown color. There is an old Japanese saying that "water in bizenware does not go bad". This is probably due to the high mineral content of the clay, which helps to purify the water and even improve the taste.

Hattan Nishiki No.1 Rice (八反錦1号)

Hattan-type rice from Hiroshima dates back to 1875, when private growers cultivated rice based on Hattansō.

A short time later, in 1907, the Hiroshima Prefectural Agricultural Experiment Station began producing higher quality Hattan-type rice varieties. The main goal for the improved strain was a rice with a clearer shinpaku, better disease resistance and higher yield.

There are three main varieties in the "Hattan family," all three of which are descended from the historic Hattansō variety: Hattan 35 (1962), Hattan Nishiki 1, and Hattan Nishiki 2 (1984). Varieties 1 and 2 have a larger shinpaku and are more suitable for sake brewing. Both Hattan Nishiki No. 1 and No. 2 break easily when polished, while Hattan No. 35 has a smaller, harder shinpaku that does not break as easily. The degree of breakage for No. 1 and No. 2 makes them unsuitable for high gloss brewing of Ginjō and Daiginjō, so only Hattan No. 35 is used for this purpose.

Sake from Hattan Nishiki 1 and Hattan Nishiki 2 show a subtle, velvety aromatic profile, but have a rich, earthy flavor and mild texture.

Tamasakae rice

Tamasakae (玉栄) is popular in its native Shiga and Tottori. More modest quantities also come from Yamanashi and Wakayama.

It is genetically a cross between Yamasakae and Shiragiku and relatively difficult to cultivate. As a result, production has increasingly declined in favor of more Ginjō-friendly rice varieties. Since there are other, more kōji-friendly rice varieties, Tamasakae's use for brewing Ginjō-shu is severely limited.

Tamasakae rice has very large grains, but a moderately large shinpaku (25-60%) and relatively low protein. It is well suited for making dry sake with a crisp finish. Sake made with Tamasakae tends to be soft-textured, rich in flavor, somewhat savory, smooth and complex.

Dewa San San Rice

Dewa San San (出羽燦々) (Dewa 33) was first cultivated in Yamagata in 1985 and originally crossed from Hanafubuki and Miyama Nishiki. It was officially registered in 1997. In terms of quantity produced, it ranks 8th in total Japanese Shuzō-Kōtekimai production.

To qualify for the Dewa San San label, brewers must meet certain standards:

- 100% Yamagata rice "Dewa San San" use

- Sake must be Junmai Ginjō quality and polished to at least 55%

- Yamagata yeast and original Yamagata-Kōji (Oryzae Yamagata) must be used

Sake made from Dewa San San rice is usually fragrant, often sweeter than dry, mostly spicy & complex, and can range from fruity to earthy.

The bottles are clearly marked with a blue sticker, so Dewa 33 sake from Yamagata is always easy to find.

By the way: Yamagata Prefecture was one of the first regions to receive GI certification (Geographical Indication = controlled designation of origin, roughly comparable to the "DOCG" label (or IGP label) of Italian wines; see also our chapter on "Water").

Examples of sake rice varieties that are not Shuzō-Kōtekimai

Ōseto rice

Sake made from Ōseto rice is strong in character and rich in umami. The flavors are subtle, and the finish is clean and crisp. Ōseto is not a Shuzō-Kōtekimai, can be used for the production of quality sake. It is as popular for sushi as it is for brewing sake.

Ōseto is grown mainly in Kagawa, but occasionally on the island of Shikoku. Its grains are relatively small and high in protein. It compensates for its small grain size with high yields and its dry (non-sticky) nature. The genetic strain is the result of crossing Nakei 212 and Kochikaze. It was first used for sake production around 1980. A typical and special sake brewery for this is Ayakiku (Kagawa), which uses only Ōseto rice in its sake.

Kame no O rice

Kame no O was discovered in Yamagata around 1900 and spread very quickly due to its quality and resistance to cold.

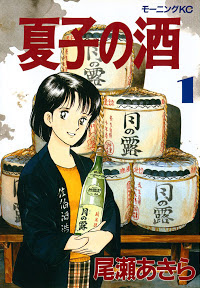

However, the tall rice is fragile and susceptible to wind damage. Due to its fragile nature, it must be carefully cultivated by hand. It is also susceptible to pests. For this reason, Kame no O fell out of favor and disappeared completely in the 1950s. In the 1980s, Kusumi Shuzō of Niigata revived it with a handful of seeds from a seed bank. It took three years to grow enough grain to produce sake.

The events were so interesting that they even spawned a manga: Natsuko no Sake!

Kame no O has spread from Niigata back to Yamagata and is now also grown in Kanagawa and Akita.

Sake from Kame no O often has a somewhat muted aromatic intensity, but a rich, citrusy flavor profile. It tends toward the dry side and is often earthy with umami that lingers on the palate. The acidity can be elevated and has sour cream or yogurt notes.

Surely there are many more varieties of rice from which you can brew sake or one of which you can tell an interesting story. Are you interested in them? Share this page, let us know - or let us know, if you are missing any info worth telling. We look forward to your feedback and your visit to our restaurant sansaro!